My Experience With Vue 3 and Typescript So Far

Published on 22. October 2020

I recently started working on the user interface for Pirsch and was very happy to hear that Vue 3 has been officially released and marked production-ready. While most of the other core libraries, like vue-router and vuex, are still in beta, I didn't want to build upon Vue 2. Don't get me wrong, Vue 2 is a great framework and stable, but I wasn't satisfied with my approach to building frontends anymore.

This article is about the transition to a new project setup, my first steps in Vue 3, and the experiences I made using it together with TypeScript. I will provide code samples and highlight a few features I found useful and refreshing.

Some Background

I started learning Vue back when they made the transition from version 1 to 2 and I quickly built my own setup, ignoring the default way of setting up a project through the vue-cli. This time, however, I wanted to just use what's there and not wrap my head around setting up stuff like webpack. Additionally, I wanted to try out TypeScript, something I have shied away from for a long time, mostly because I believed it would add an additional layer of abstraction on top of vanilla JavaScript, which seemed unnecessary to me. And as we recently started developing a new product called Pirsch, which has a fairly simple frontend, I took the opportunity to try out something new. As I'm a beginner with TypeScript, please let me know if you find anything odd or plain wrong.

Setup

The best way to set up a new Vue 3 project is by installing and using the vue-cli.

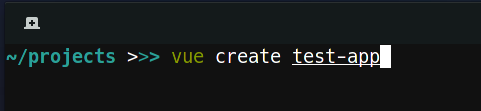

Run vue create <name> to set up a new project.

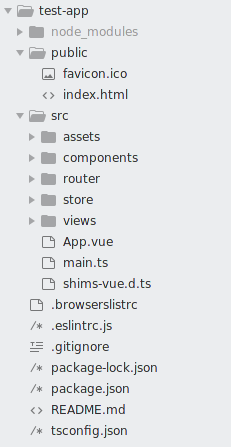

This command will generate a new project inside the test-app directory and create the basic structure. Note that you will have to select Vue 3 and TypeScript from the Manually select features option at the beginning, as it is still marked as experimental.

Out-of-the-box project structure of a new Vue 3 project.

Nothing surprising so far, but what really astonished me was how well everything works out of the box. I used to have two commands, one for building the Vue app itself and one to compile the Sass files. With this new setup, I could just place the files inside the public directory, and they would be automatically compiled to CSS.

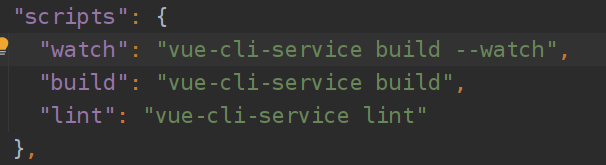

The only changes I made were removing the assets folder and adding a command to the package.json to rebuild when something changed (build is still used for the production release).

A very lean package.json.

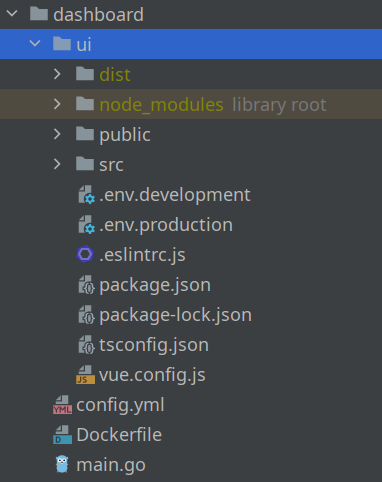

I use to embed my apps inside a custom Go server, to have control over configuration, headers, how files are served, easier deployment, and to add some functionality of course. By default, the build and watch commands will put the compiled files into the dist folder, present inside the root directory. The app itself is a subdirectory of the Go server.

Before, I just served the whole UI directory, but this time I had to select the directories under dist to make it work.

server.ServeStaticFiles(router, "/js/", "ui/dist/js")

server.ServeStaticFiles(router, "/css/", "ui/dist/css")

server.ServeStaticFiles(router, "/img/", "ui/dist/img")

server.ServeStaticFiles(router, "/fonts/", "ui/dist/fonts")

router.HandleFunc("/favicon.ico", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

http.ServeFile(w, r, "ui/dist/favicon.ico")

})

router.PathPrefix("/").HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

http.ServeFile(w, r, "ui/dist/index.html")

})

Note that each sub-directory of ui/public will create a directory inside dist, so you need to add it to the router in Go. favicon and index.html are the only special files I have so far. The index is served last, as it needs to be sent no matter what page the visitor is on. If someone visits yourdomain.com/foo/bar the server would otherwise try to find an index file inside foo/bar.

The Composition API

You might have heard about the Composition API already. It's a new way to define the structure and behavior of a component, living alongside the traditional way of defining a component using the object notation. I started out setting the goal to just use the Composition API, as the videos I've seen about it looked very promising. You can still use the traditional way to define your components, but so far, I'm very pleased with it. In case you plan to upgrade from Vue 2, you don't need to re-write everything. But if you start a new project, I would recommend you go ahead and use it right from the beginning.

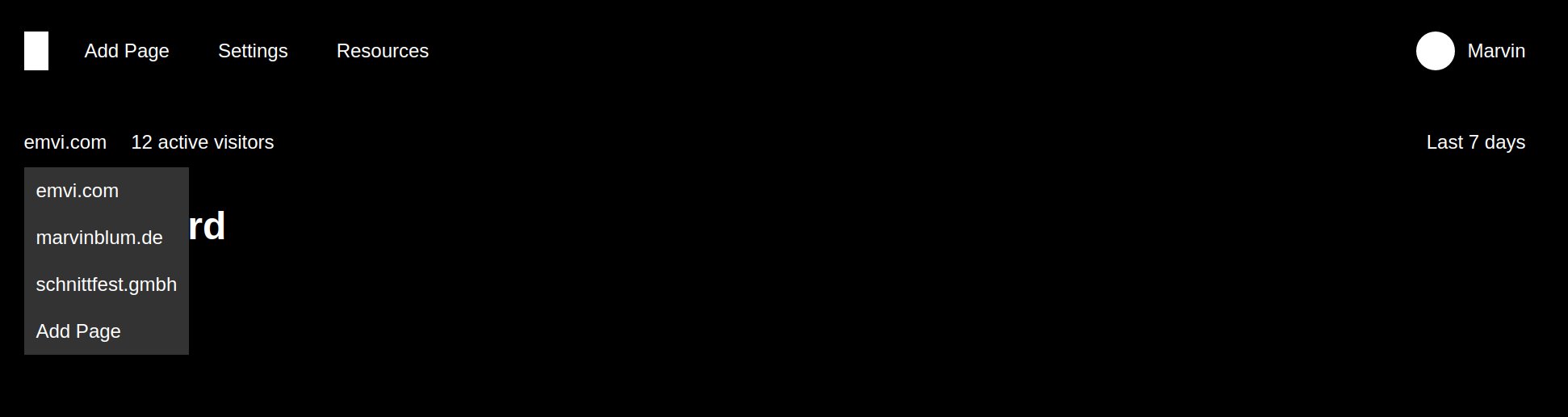

I fell in love with it when I had to implement multiple dropdowns. Here is an example from Pirsch, when I built the menu and had to add four dropdowns, which are functionality-wise all the same.

An early version of Pirsch's menu.

There is a dropdown for the domain, the resources, the time frame, and on your account. Functionally they're all the same. You click on the menu entry and it opens up. If you click anywhere outside the dropdown, it will close. One way to approach this problem would be to create one component and reuse it everywhere, but in this case, the HTML structure is slightly different. With the new Composition API, you can outsource this problem into its own file and function and just use it inside the components you need it.

import {ref, Ref} from "vue";

// This defines which attributes and functions will be available to the component.

interface Dropdown {

dropdownElement: Ref<HTMLElement>

dropdown: Ref<boolean>

toggleDropdown(): void

}

// And this is the re-usable function which will be called from the components.

export function useDropdown(): Dropdown {

const dropdownElement = ref(document.createElement("div"));

const dropdown = ref(false);

function toggleDropdown() {

dropdown.value = !dropdown.value;

}

window.addEventListener("mouseup", e => {

const element = dropdownElement.value;

if(/* ... */) {

dropdown.value = false;

}

});

return {

dropdownElement,

dropdown,

toggleDropdown

};

}

As an example, this is the domain selection you can see on the screenshot above.

<template>

<div class="selection cursor-pointer" v-on:click="toggleDropdown" ref="dropdownElement">

<span>{{activeDomain.hostname}}</span>

<div class="dropdown" v-show="dropdown">

<div v-for="domain in domains"

:key="domain.id"

v-on:click="switchDomain(domain)">{{domain.hostname}}</div>

</div>

</div>

</template>

<script lang="ts">

import /* ... */;

export default defineComponent({

setup() {

/* ... */

return {

...useDropdown(),

/* ... */

};

}

});

</script>

All it takes is to add the function to the return statement of the setup function and boom! You can use the functionality inside the template. I have more examples like this, but I think you get the idea.

Component Structure

Another major benefit of the Composition API is, that you can now structure the code the way you want it. A component might take up hundreds of lines, depending on the complexity of your app (which should not happen that easily anymore, thanks to the Composition API) and you had to separate the data, methods, and other parts in a certain way. Editing large components naturally included a lot of scrolling and not seeing the data you were working with inside a method for example. Now, however, you can define the data right above the function you're using it in and mix it up. So instead of having something like this.

<template>

<!-- lots of code -->

</template>

<script>

import /* ... */;

export default {

data() {

return {

foo: 42,

/* far away from each other! */

bar: ""

};

},

/* maybe even more code */

methods: {

methodA() {

this.foo++;

},

/* 500 lines of code */

methodB() {

this.bar = "Hello World!";

}

}

}

</script>

You can now keep it easier to read.

<template>

<!-- lots of code -->

</template>

<script lang="ts">

import /* ... */;

export default defineComponent({

setup() {

const foo = ref(42);

function methodA() {

foo.value++;

}

/* 500 lines of code */

const bar = ref("");

function methodB() {

bar.value = "Hello World!";

}

return {

foo,

methodA,

bar,

methodB

};

}

});

</script>

And you might not even need to expose all data to the template. Imagine foo just being used internally. You still would have had to define that in data to access it. Now, you can just use a regular variable inside setup.

Generics With Typescript

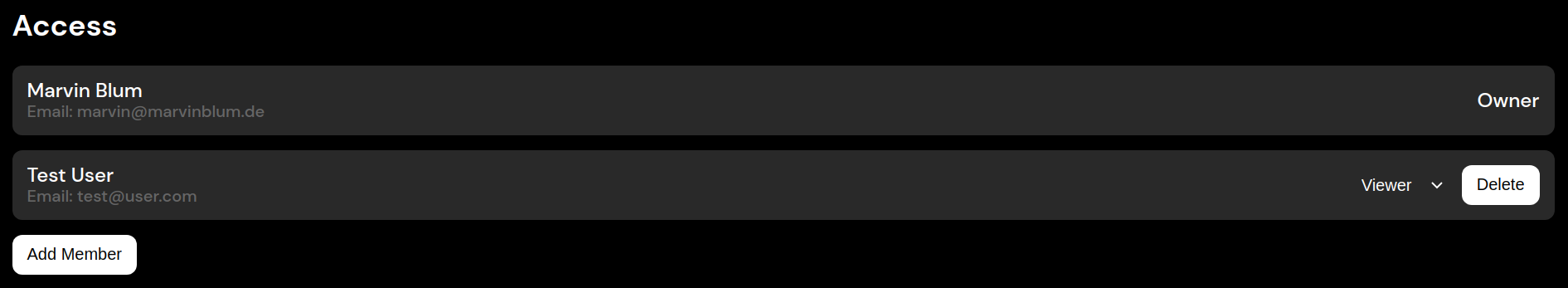

Another moment I felt pretty good about my choice using TypeScript, was when I had to implement lists. Lists are often used to display data that would otherwise be in a table. They usually consist of "cards" in my apps, showing what it is and some additional fields and buttons to edit or remove them from the list.

I know this doesn't look very nice at the moment...

As lists are used across the page, I didn't want to re-implement them over and over again. You probably can guess that I used the composition API to implement the behavior, but this time it had to be generic.

TypeScript strength is to... you know... check types. So we want to build a type save reusable function. As you can see above, it needs to support the User type, and there is the Client type too. To do that, you can make use of generics.

interface ListEntry {

id: number

}

interface List<T extends ListEntry> {

/* ... */

}

export function useList<T extends ListEntry>(): List<T> {

const entries = ref<T[]>([]);

const selectedEntry = ref<T>();

/* */

return {

entries,

selectedEntry,

/* ... */

};

}

The import part here is the ListEntry which defines an interface for all entities in my application. They all have an ID, which is used for the :key attribute in Vue and also to add and remove entries from the list. Here is how you would make use of it.

setup() {

const {entries, addEntry, removeEntry /* ... */} = useList<User>();

/* ... */

return {

entries,

addEntry,

removeEntry,

/* ... */

};

}

Templating

The templating stayed mostly the same, but there are a few changes which made me enjoy Vue 3 even more. One that stood out to me was, that you no longer need to have a root element for all of your components. So defining the template of a component like this is fine.

<template>

<h2>Email</h2>

<form v-on:submit.prevent="save">

<FormInput label="Email Address" name="email" type="email" v-model="email" :err="validationError('email')" />

<FormSubmit value="Save" />

</form>

</template>

<script lang="ts">

/* ... */

</script>

This might not seem significant at first glance, but it sometimes got annoying in Vue 2 that you had to add a root element artificially to your component, even though it wasn't required for styling nor structure.

Conclusion

There is a lot more I could talk about, like having a linter to keep your code clean, but I think this is enough for now. I might write a follow-up when I have more experience with Vue 3 and TypeScript. I refused to make the switch to what is probably considered a best practice for quite some time. If you're someone like me who needs to know how everything works, even the project setup, make sure you don't waste time doing that and spend it on building something useful instead.

In case you got inspired to try out Vue 3 now, you can read the introduction, which shows the major and minor differences between Vue 2 and 3 far better than I could.